Integrated

AUTHOR

Business Director

Ben is an accomplished digital strategist with 7 years of expertise across diverse verticals. Renowned for his proficiency, Ben seamlessly combines unwavering enthusiasm with a nuanced understanding of client growth. His dynamic approach ensures consistent excellence in navigating various digital landscapes.

SHARE

OVERVIEW

INTRODUCTION.

All online businesses strive for growth, and most will commonly attempt to attribute sales or conversions to specific digital marketing channels (like organic search or social media) in order to understand and manage budget and performance. But deciding which specific channel to assign a sale to — when users frequently visit from multiple channels (and devices, locations, times, and so on), in a way which provides insight and value, is complex and difficult.

How does one measure which channels were most influential in purchase decisions? Was the first or the last touch point more important? What happens if there are offline touch points, too? These are hard questions to answer, and the complexity increases with each channel that is added to the mix.

Making the wrong decision means wasting budget, missing out on sales or cannibalising broader efforts – effectively hindering business growth. As a result, digital marketers and analysts turn to different methods and models of multi-channel attribution to attempt to understand the value of each channel in isolation, and how user behaviour and consumer value changes when they interact with each other. They model scenarios that apply different values depending on the ordering, role or behaviour of a specific channel within a user journey; all of which are ‘true’, but none of which agree on the value of any given vertical.

Given this complexity, it seems counter-intuitive to build strategies for each channel in isolation. When deploying tactics and activity, and measuring the performance of a specific channel, there is a risk of negatively impacting other channels, and even harming overall performance. What is more, the chances are, you probably do not even know it is happening.

When budgets and individual key performance indicators (KPIs) — and, frequently, performance-related bonuses — are allocated by channel, there is a risk of reducing the incentive to collaborate on integrated strategies. It is every person for themselves, in a rat race to prove that their channel performs best — all at the expense of the consumer, and the business’s growth aspirations.

In almost all cases, channels could perform better if used efficiently together — and while there may be short-term losses in some areas, as the distribution of traffic and conversions shifts to a smarter equilibrium, there are significant opportunities to be had by working together.

Anyone who wants to fulfill their growth ambitions must put the overall business objectives first and worry less about individual channel budgets, performance and bragging rights. This means building integrated growth strategies that span different activities, departments and verticals.

To apply this kind of thinking, it is essential to align and integrate all aspects of one’s strategy and tactics, from defining and developing objectives; to changing how to research the markets, audience and competitors; to how to position and market products and services.

The more sophisticated the planning at each of these stages and the better quality of data and research applied, the greater the chance of deploying a successful multi-channel strategy. This is a huge challenge, with many moving parts; there is a reason why most brands do not achieve this level of cohesive, cross-channel marketing. Nonetheless, this article explores some of the key processes, milestones and frameworks that must be developed in order to seize the potential of a multi-channel strategy. This should be a starting point for connecting the dots, and capitalising on the growth opportunities.

SHAPING OBJECTIVES.

The starting point of any successful growth marketing strategy is establishing the core objective — defining what you are trying to achieve.

Chad Storlie, alongside many other well-known leaders, discusses the setting of such objectives using a premise referred to as ‘commander’s intent’. Storlie writes:

‘The role of commander’s intent is to empower subordinates and guide their initiative and improvisation as they adapt the plan to the changed battlefield environment. Commander’s intent empowers initiative, improvisation and adaptation by providing guidance of what a successful conclusion looks like. Commander’s intent is vital in chaotic, demanding and dynamic environments’.

By framing objectives in terms of the desired outcome, rather than specific directives, everybody in an organisation — regardless of their channel expertise or responsibility — can align to a single vision and definition of success.

To apply this thinking throughout an organisation, one can view the subordinates as the stakeholders of each individual channel within the marketing mix. With this context, the overarching objectives (the commander’s intent) must not be channel-specific; instead they must relate to business goals, and it is up to the individuals involved to identify the best distribution of effort and resources across each channel to reach this goal. While individual channels, such as pay per click, may be targeting a set cost per acquisition or other metric, ultimately this is decided upon as a means to tie back to the overall organisation’s commander’s intent. This allows those within the channel to determine day-to-day metrics and smaller goals to contribute towards the bigger picture.

When individuals are motivated to pursue meaningful, overall success — rather than specific metrics relating to their own share of ownership — they can make braver decisions with greater impact and work more effectively across boundaries and outside of silos.

SINGLE-CHANNEL OBJECTIVES.

Setting channel objectives that relate directly to business targets may seem self-evident, yet this action is frequently forgotten.

In the case of organic search, for example, ambitions and objectives frequently relate to improving rankings or traffic for specific keywords, rather than relating to fulfilling the searcher’s intent and meeting their needs.

In biddable media, activity must often meet an acceptable cost-per-action (or similar metric), which prohibits targeting or engaging with any users other than those who are ‘at the bottom of the funnel’ because, users who are researching and building consideration sets tend not to convert directly through that channel.

These are both examples of where a channel-centric focus might miss the point — the goals of the organisation are to capture demand and to acquire the customer, but the requirement for each channel to be measured successfully and perform in its own right can compromise overall performance — or at least, can come with an opportunity cost where the real potential is never reached.

By eliminating a single-channel focus when setting objectives, it prepares the multiple stakeholders within a marketing team to approach the task as one unit, rather than working (and competing against each other) in isolation.

By using the commander’s intent rather than channel-centric goals, individuals and teams can put the business’s growth interests at the forefront of their strategy.

MARKET RESEARCH.

To execute a successful marketing strategy, it is vital to have an understanding of the complex ecosystem within which the business is operating.

Each market and industry will have its own quirks and characteristics, all of which must be acknowledged in order to ensure the strategy is actionable and impactful. Effective research makes it possible to:

- quantify the size of the opportunity

- understand industry trends

- deconstruct competitor strategies

- identify the value being brought to and the consumer over competitors.

SIZING THE OPPORTUNITY.

To determine whether the market is growing or shrinking, and successfully analyse the particular peaks and troughs in its popularity, organic data sources must be accessed in order to provide the best information.

Assuming that the trends in which people search for topics and solutions is a reliable proxy for the size of interest in a market or product,

Google Trends (https://trends.google.co.uk/trends/) and the Google AdWords Keyword Planner (https://adwords.google.com/KeywordPlanner) are excellent tools for sizing the opportunity.

DECONSTRUCTING COMPETITOR STRATEGIES.

In a perfect market, filled with rational actions and perfect knowledge, a brand could generate its own demand and inspire people to know their products and to purchase them. The real world, however, is more complex and less rational.

Markets have finite sizes, consumers act emotionally and irrationally, and simply growing market share rather than fighting tooth-and-claw is tough. Growing audiences and introducing new consumers into a market can be challenging and expensive. Consumers who are already in the market may be price-driven, may have existing (competitor) brand preferences, and are frequently exposed to messaging from multiple channels. It is hard to grow audiences and to access new opportunities.

When it comes to weighing up these options, the most effective way to gain market share is often through taking consumers from competitors (or, at least, stealing consumers while they are still in the consideration and research processes).

To take market share effectively requires a foundation of strategic and competitive differentiation — but there are frequently tactical opportunities around specific channels.

In paid search, organic search and affiliate marketing, there is a surprising degree of competitive intelligence and transparency available. Tools like SEMrush, SearchMetrics and Luminr can analyse competitor spend and performance from the outside-in, which might shed some insight into key competitors’ strategy.

Having analysed what competitors are doing well (or not so well), it is possible to characterise their strategies. It is useful to go through a process of summarising this as a single paragraph, written from their perspective in the first person. This becomes a powerful addition to one’s commander’s intent — it is a glimpse into the enemy’s strategy, and an added dimension for one’s subordinates to consider.

DEFINING A UNIQUE VALUE PROPOSITION.

Armed with market understanding and a broad view on competitor strategies, the next step is to identify where one’s brand fits within that environment.

Seth Godin describes it as ‘finding your purple cow’ — or establishing those key elements that make a brand stand out from its competitors.

Historically, marketing involved defining a unique selling proposition; now, with consumers increasingly taking control of their education and research processes, it is essential to define a unique value proposition — the competitive positioning and storytelling that makes people want to believe in the brand and your vision.

Getting to grips with the unique value proposition is an important component of defining the commander’s intent; without the context that differentiates the brand and defines its value, there is a risk of the commander’s intent being weak, subject to competitive threat, and internally focused.

When this is the case, it only takes one competitor in the marketplace to have a consumer-centric, externally focused commander’s intent and value proposition for them to erode your market share, simply by using the types of data and tactics explored above.

FINDING WHAT CONSUMERS THINK THEY WANT.

One of the methods by which a brand may dominate a disproportionately large market share is through understanding what consumers are looking for, the specific mechanics of how they enter a market, how they search, and how they build consideration sets and make decisions. This is powerful insight, which can be used to shape strategies, proposition and positioning.

However good a product may be, if one takes a solely insular view towards its marketing, then it is unlikely to be successful. For the product to have a chance of exponential growth, the marketing approach must take into account the external views on the product.

This means not only producing a product that consumers want, but also understanding what they think they want.

“This means not only producing a product that consumers want, but also understanding what they think they want.”

The output from this is knowing how consumers refer to the product, the elements they are searching for in their journey to purchase, and what related topics they will also be looking at. Typically, this means specific data and insight into search behaviour, the types of things users search for, and the brands, websites and content that users see when they conduct that research.

THE EROSION OF SEARCH DATA.

The primary point of research will be to understand how users refer to the product, and how they understand its purpose.

In search — organic and paid — this has become increasingly difficult, with Google restricting the more accurate measurements that could once be obtained on search volumes.

The grouping of keywords in Google Keyword Planner, combined with the removal of most keywords in the organic traffic reporting for Google Analytics, has hindered marketers’ ability to know how consumers are looking for their products.

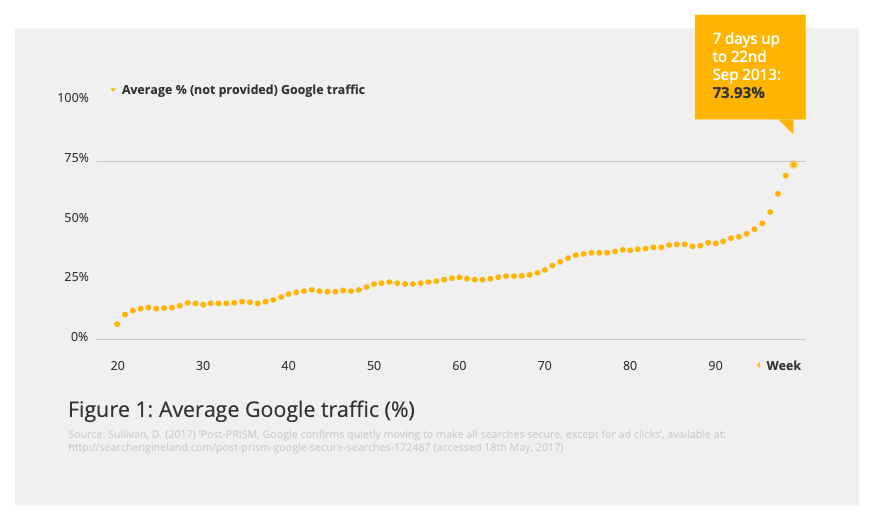

It was in 2011 that Google began encrypting the searches of logged-in users; preventing the data on the queries generating traffic for a site from being tracked in Google Analytics. Instead, (not provided) began to be commonplace in the keyword data available through Google’s tracking platform.

Just one year on and Google began to encrypt more and more queries, even from users who were not logged in, and soon the percentage of (not provided) traffic spiked and sites such as Not Provided Count reported that approximately 73.93 per cent of queries were encrypted by September 2013; as shown in Figure 1.

With regard to search, the other key tool for identifying the way in which consumers are searching for a product or service is Google’s Keyword Planner. In 2016, Google began to use aggregate search volumes for similar terms, eg plurals, synonyms and with/without spaces, which significantly changed the data being returned to marketers. The impact on those using the data was outlined by Jennifer Slegg:

‘For those that do not notice the change — or worse, pulling the data from tools that haven’t updated to take into account the change — this means that some advertisers and SEOs are grossly overestimating those numbers, since many tools will combine data, and there is no notification alert on the results to show that how Google calculates average monthly searches has been changed’.

These changes have limited marketers’ ability to identify accurately how consumers are finding their products online.

There used to be an easy way to capture these statistics, but marketers must now work harder to find the conversations that potential customers are having before they even start considering how to align a brand to meet these needs.

UTILISING SOCIAL MEDIA.

While there has been a loss in access to data from these developments, a separate trend on the rise is the use of social media to analyse consumer intent and needs.

With over 2.38 billion users on Facebook, 330 million on Twitter and 1 billion on Instagram, potential consumers are no longer just using search engines during their purchase journey, but instead will be asking their friends and connections for advice and recommendations on these platforms too.

The scope of the data available across all social media platforms is far greater than that of a simple keyword list. The tagging functionality, such as hashtags, that enables social media to be straight-forward to browse also enables marketers to access a wealth of information in the way consumers are communicating.

SCRAPE RELATE TERMS.

Pinterest is one of the social networks in which the biggest interface changes have been seen over the past year. Specifically, there have been significant developments in the search functionality as shown below, and on the back of this, a wider scope of data accessible.

By collating such data, a clear picture of topics people are most engaging with, and ways to expand from an initial keyword set and into long-tail opportunities, becomes evident.

The most effective way of capturing this insight is to utilise a scraper. An excellent Chrome Extension for this is Data Miner — a scraping tool pre- loaded with ‘recipes’ for popular sites. One of the standard recipes is ‘Pinterest Related KWs’ which will produce a list of all the related keywords on a search, all presented in a downloadable CSV.

The same plugin is effective for identifying hashtags and popular tweets on Twitter; using the available public recipes (or customised rules) one can export the hashtags, share counts or users within lists or searches conducted.

For example, to determine recent trends in the topics discussed at search engine optimisation (SEO) conferences, an export of the speakers’ Twitter lists can be used to count the number of times specific keywords (eg content, AMP or PWA) are mentioned. This will produce a simple, accessible view of the most commonly discussed themes.

The hardest challenge for brands is to understand the external perception of their product, and to be able to understand how consumers view their purchase funnel. The ability to evaluate their own performance in this way enables brands to begin to operate in a significantly more consumer-centric way.

The key here is that consumers do not browse and engage on a single channel, hence brands must also operate across multiple channels when building the relationship between themselves and consumers.

UNDERSTANDING SINGLE COMSUMERS.

Fundamentally, the top-level aim of any business is to convert consumers into customers.

Analysis into search or social data on how consumers find one’s product looks at these individuals as a collective group. However, it is also important to identify how the individual user’s journey takes place.

This means understanding the way in which those consumers browse and interact with brands through every stage of the purchase funnel, and ensuring the brand is present at each point. For tracking purposes, the perfect consumer would browse rationally on a single device, in one session — however, this is never the case. Instead, marketers face multi-device shopping patterns and frequently irrational consumer decisions.

This irrational browsing behaviour makes it harder and harder to track and understand the way in which consumers are moving through the purchase funnel.

MULTI-DEVICE BROWSING.

The majority of consumers, in particular in UK and US markets, now own multiple devices on which part of their purchase journey may take place. Whether it is browsing on a mobile during their morning commute or on a tablet in the evenings, before purchasing at their desktop during the day or conducting the full research-to-conversion process on their mobile device — there is now a huge potential for marketers to lose track of their consumers during the purchase funnel.

Every point where a user changes the device on which they are searching is a risk to brands trying to build a clear vision of the purchase funnel. This leaves marketers and attribution specialists attempting to cross-stitch user sessions over devices to identify who the same individuals are. The accuracy of this varies wildly depending on the tracking methods chosen, thereby hindering the ability to understand the true consumer journey.

Not only has there been an increase in the use of multiple devices through the purchase funnel, but there has also been significant rise in the number of people using multiple screens at once. Consumers will not just be watching television, but will also be using their smartphones or tablets at the same time.

This poses the challenge of conducting strategies that are able to account for the behaviour of users across multiple devices.

Part of this challenge is that due to data protection legislation, and of course Google’s own restrictive policies, many of the ways that a brand might be able to match its customers across different devices are severely inhibited — or simply not possible at all. In particular, when measuring organic channel performance, attempting to follow consumers through their cross-device journey is essentially impossible.

On top of this, considerations must be made for the fact that although there is a comparatively high amount of browsing seen on mobile devices within early consumer journey stages, this in itself is not a reliable proxy or indication of consumer buying power.

To capture the true value of mobile traffic, one cannot assume that targeting mobile users early on in the consideration process is a good use of client budget.

RETARGETING ACROSS DEVICES.

Data from attribution platform CUBED Attribution indicate that the value that organic marketing receives in a last-click attribution model (where organic is the last interaction before conversion) is sometimes undervalued by at least 20 per cent, in terms of its contribution to conversions.

Content higher up the funnel, usually in the form of content marketing, can be effective in engaging with consumers during the awareness and consideration phases — but due to difficulties in attributing organic, this form of marketing is frequently undervalued.

This is because as users move across devices, it is only through techniques such as paid media retargeting that brands are able to follow their customers accurately. As a result, the value of the conversion is frequently credited to the paid media channels only.

Despite the difficulties in how to attribute the value of journeys such as this, paid retargeting provides a simple method for ensuring that a brand is visible at every stage in the purchase funnel.

In particular, using the Facebook retargeting pixel is extremely effective at tracking users across their full range of devices, and ensuring that a brand is kept in the forefront of their mind — even subconsciously.

If your consumers are typically visiting your site many times and from a range of devices before making the commitment of purchasing, then a holistic approach to retargeting will ensure that brand presence is maintained throughout their journey to purchase.

Struq (now owned by Quantcast) identified a significant increase in conversion rate when retargeting was operating across multiple devices, and following the path of the user.

For organic search marketers, the information that paid targeting and retargeting campaigns provides can be especially useful. Without access to reliable cross-device data, this is an acceptable method of seeing the type of content consumers react best to and what kind of buying objections the brand may face.

Equipped with this information, an organic strategy can be sculpted to provide effective onsite content based on the sponsored content that users responded best to on their cross-device journey. In a multi-channel strategy world, there would be fewer difficulties in attributing the exact values of the content here.

BUILDING A STRATEGY.

Research and analysis alone is not a strategy. The final stage is the most significant — where all learnings must be combined into measurable and convincing actions.

Interpreting the data collected and refining the findings or research into a true strategy is not a simple task. Nor, admittedly, is there a single answer to how to do this. This is an element of marketing that requires creativity, experience and just a little bit of luck to create a successful strategy.

The methods outlined in this paper are based on the premise of having an existing understanding of how to create a strategy, then how to take this one step further by broadening its scope across channels.

The transition to approaching marketing as a whole, rather than by channel, is not going to be a fast one. It is intrinsically built into the way that success is measured and rewarded that accountability sits with each channel manager individually, rather than a single marketing team.

It is because of this that the growth of digital marketing as a whole is being hindered, leading to the disenchantment of so many brands. With strategies where each channel is self-interested, success may be smaller or less efficient to reach, and therefore the appropriate distribution of resources is never made.

By fiercely defending channels in isolation, instead of supporting the growth of marketing as one entity, the result is a distortion in marketing data.

ORGANISATION CHECKLIST.

While it is easy to see the efficiencies that may be gained through approaching a strategy in this way, if the structure of the organisation does not allow for this type of evolution then implementation will take time. An agile organisation will be required to be able to respond to the increasing need for channel integration, while still motivating the individuals within the team.

The requirements for a successful multi-channel marketing and growth strategy are:

- clear vision for the end goal

- single marketing budget

- cross-channel internal KPIs

- knowledge across all marketing channels

- excellent communication between specialists

- and regular reviews of strategy and performance.

CLEAR VISION.

The starting point of any successful strategy must be to know what success is going to look like at the end. Identifying a core statement to aim towards enables a more agile adaptation of different tactics as required, and an iterative strategy that is more likely to be successful.

SINGLE MARKETING BUDGET.

One of the biggest adjustments required is on the way the financial department will operate.

Previously, most brands managed their marketing budgets through individual channels, assigning management fees and advertising spends where return on investment has been demonstrated historically. Similarly, the compensation offered to staff for the value they add to the business becomes more complex to determine when objectives require all teams to work together to achieve them.

Directly matching the revenue from each traffic source to the amount of money invested in the future will no longer be a suitable method of allocating budgets.

For those operating within finance, understanding the intricacies of a cross-channel marketing department and then making appropriate decisions on administering the budget will become too large a challenge.

Preparing an organisation to be able to operate in this manner will require a single marketing budget, negotiated and distributed among the specialists themselves.

CROSS-CHANNEL KPIS.

The third, and final, key structural roadblock is the motivation of individuals within the organisation.

It would be unfeasible to assume that all individuals within the marketing team could be trained across all channels, which means the success in team performance will be significantly more interdependent than at present. Accountability related to success will be difficult to define when the channels are working so closely together.

KNOWLEDGE ACROSS ALL MARKETING CHANNELS.

If the organisation’s team is small, or heavily weighted in favour of one channel, it may be a challenge to identify the best combination of tactics to achieve the objectives.

It is natural for experts within their field to be biased towards their specialism as having the greatest impact or being the most successful at generating results — this passion for their skill set is what makes these individuals become experts. However, a narrow view of the marketing ecosystem can create biased strategies that may not be the best for the brand.

To be successful at building a fully integrated marketing strategy, the team must have a balanced mix of knowledge across multiple disciplines. This is one of the largest challenges when building a team.

Working with agencies or freelancers to fill gaps in one’s skill set could be an effective method for bridging the knowledge gap. However, these parties will also be interested in upselling their activities and include further biases.

There is no simple solution to this difficulty, and it is unlikely that there will ever be a ‘perfect’ solution when developing a team. An awareness of this challenge, stakeholders’ biases and the knowledge deficit within one’s organisation will help to acknowledge the risks in one’s multi-channel strategy.

COMMUNICATION.

Project management must operate across channels too, assigning resources and time effectively across the multiple channels. In turn, this influences who to hire, and which skills to focus on first when training within the team.

Depending on the method of project management within the organisation, the size of the team participating will need to increase; if working to agile methods then this may translate as a significant strain on resources.

A pragmatic approach will be to find a new way to structure the sub-teams within the marketing department; for example, product marketing teams focused on a single product range with specialisms across all channels, rather than dividing on a channel basis.

REGULAR STRATEGY REVIEWS.

Within the implementation process of any marketing strategy there will be multiple factors beyond the control of the organisation. From the work of competitors, to algorithm updates or a shift in demand, there are many external influences upon the success of a strategy.

This means it is crucial to hold regular performance reviews, and to be willing to adapt the strategy at any point. While this is vital in single-channel strategies too, it becomes more important when looking across multiple channels as external changes could mean a missed opportunity as well.

For example, if a competitor ceases all paid media activity but the strategy being implemented is predominantly on organic channels, then there should be a reassessment of the tactics currently employed.

CONCLUSION.

Changing the way that one guides, motivates, incentivises and rewards teams and individuals is challenging. It requires careful planning, and a broad foundation of data and research upon which one can build a robust strategy and differentiated messaging.

Without this foundation, however, there is a risk of rewarding teams and channels for actively competing with each other, and cannibalising the orgnaisation’s efforts.

Competing brands — those who inspire their teams with commander’s intent, rather than giving them KPIs relating to their specific channels — will find it disproportionately easy to take market share, and ultimately erode market presence.

It is important to remember that marketers are here to position brands and products effectively to consumers. As a result, it is essential to build strategies that work together in order to maximise the value to the business and to consumers. For this to happen, the strategy must be founded in research — from the market, competitors and consumers.

As marketers’ ability to attribute actions to individuals grows, this research will look not just at the broad ‘consumer’ audience, but also much closer at niche persona groups. The data that marketers unearth during this stage make it possible to construct effective strategy that will help businesses to reach their desired commander’s intent.

Consumers behave in irrational ways, and their digital habits are subject to change based on the latest technology trends. As a result, marketing methods must remain sufficiently agile to adapt to the ever-changing consumer needs and actions — hence the importance of regular strategy reviews, as discussed earlier. While a strategy may be based on data, the second it is created, it becomes outdated. This signifies the importance of a fast-moving team to match the pace of change within the industry at present.

Again, organisations that run with commander’s intent, and teams that are empowered to chase organisational success — rather than costs per lead by channel — are the only ones who will be able to move fast enough to take advantage in the ever-changing digital sphere. Companies operating to a commander’s intent are able to use their clear vision and single marketing budget to make fast decisions which are best for the business as a whole.

LOOKING FOR AN INTEGRATED DIGITAL MARKETING CAMPAIGN?

We’re Found, the independent multi award-winning, digital growth agency who move fast, work smart and deliver stand-out results.

A team of growth hackers, analysts, data scientists and creatives, we design data-driven strategies to rapidly take your brand from the here and now to significant growth through frictionless user journeys.

Through our methodical data-driven approach, we find untapped, sustainable, growth opportunities for our clients.

If you would like to talk to an expert about creating an integrated digital strategy for your business, then

Ben Wheatley, Business Director - 12 Mar 2021

Tags

Data, Digital Marketing,

Date

12 Mar 2021